Autor: Shelby Benavidez

In June 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ended affirmative action, preventing colleges from using race as a factor in admissions. Many people are concerned with how this will affect culture and politics, but many schools have already found a way to admit qualified students without racial biases. So, while many people discuss the cultural or political effects, the legalities of how students are selected is the biggest change. In this article, we will break down the history of affirmative action, where it’s been used, and the federal policy changes that came afterward.

Understanding Affirmative Action and Its Role in U.S. Law

History of Affirmative Action in the U.S.

Affirmative action refers to policies designed to correct systemic inequalities by giving more opportunities to groups that have been historically treated unequal. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited explicit discrimination, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which required federal contractors to take “affirmative action” to ensure equal employment opportunities. Later, universities began considering race in admissions to build more diverse student groups, and courts allowed this but with strict limits.

En Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), the Court barred rigid racial quotas but allowed race as one of many factors. In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), it upheld the limited use of race to achieve a “compelling interest” in diversity. Fisher v. University of Texas (2013, 2016) further clarified that such policies had to be narrowly tailored and that universities bore the burden of proving no workable race-neutral alternative could achieve similar results.

Affirmative Action vs. DEI

While Affirmative action and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) are similar concepts, they aren’t the same. Affirmative action involves policies, sometimes required by law, that consider race or gender when making decisions about jobs, school admissions, or government contracts. DEI programs are wider efforts meant to make organizations more welcoming, give people fair access, and reduce bias. These programs usually focus on training, outreach, and support rather than giving advantages based on race.

That’s not to say that DEI won’t be impacted. As courts look more closely at affirmative action, some people are now questioning whether certain DEI efforts might be seen as giving indirect preferences. That issue could eventually be decided in future lawsuits.

Who Benefits the Most from Affirmative Action (Theoretically and Statistically)?

Affirmative action was meant to help racial minorities—especially Black, Hispanic, and Native American people—get access to opportunities they were often denied in the past. However, data shows that white women have actually been some of the biggest beneficiaries, mainly in areas where gender-based hiring goals were connected to racial affirmative action programs.

In higher education, the impact is more complex. Underrepresented minority enrollment increased at many selective universities, while some studies found that Asian American applicants sometimes faced higher academic thresholds. These dynamics illustrate the tension between group-based equity goals and individual fairness.

The Supreme Court’s Reversal and Federal Policy Shifts

Supreme Court 2023 Decision Explained

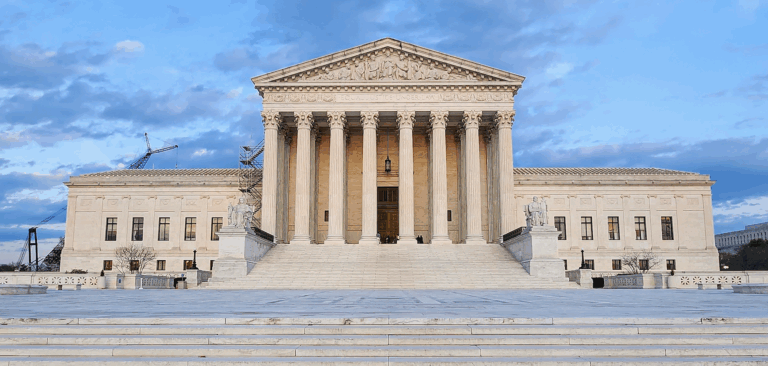

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court issued its decisions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard y Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina. The Court ruled that those universities’ race-conscious admissions programs violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that universities must treat applicants “as individuals” rather than as members of racial groups. The Court rejected the argument that diversity alone could justify continued use of race-based considerations without a defined end point.

This ruling applies to any institution, public or private, that receives federal funding. While it doesn’t prevent applicants from discussing how race shaped their lives, schools can’t give formal advantages based solely on racial identity.

Effects of Ending Affirmative Action

Universities are now required by law to design admissions systems that comply with strict race neutrality. Socioeconomic background, geography, or hardships can still be weighed, but using them as proxies for race could lead to lawsuits. Future legal disputes will likely test where the line is drawn between an applicant’s individual story and policies that indirectly attempt to maintain racial balancing.

This decision may also influence other areas over time. Opponents of workplace affirmative action programs could cite the Court’s reasoning to challenge federal contracting requirements or corporate diversity initiatives, though no ruling has yet extended this prohibition beyond education.

The Ruling’s Scope: Education vs. Employment

The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision directly affected higher education admissions. It did not change federal affirmative action requirements in employment or government contracting. Employment-based programs are governed primarily by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination but allows certain voluntary or court-ordered affirmative action measures under strict conditions.

For decades, Executive Order 11246 required federal contractors to implement affirmative action plans to ensure equal employment opportunity for minorities and women. Those requirements existed separately from college admissions policies and were not invalidated by the 2023 decision. However, the national policy shift away from race-based measures did not stop with education.

Trump’s 2025 Order Revoking EO 11246 and EO 13672

In 2025, former President Donald Trump issued an executive order revoking Executive Order 11246 and Executive Order 13672. EO 11246 had mandated affirmative action plans for federal contractors for nearly sixty years. EO 13672, signed in 2014, expanded those requirements to include sexual orientation and gender identity.

By rescinding these orders, the federal government removed long-standing contractor obligations to create affirmative action plans and eliminated explicit LGBTQ workplace protections in that context. What this means in the workplace is still unfolding, but it marks a significant policy shift: employers working on federal contracts no longer have to maintain formal diversity plans, though they are still bound by basic nondiscrimination laws. This executive action represents a direct employment-related counterpart to the Supreme Court’s education ruling, further narrowing the reach of government-enforced affirmative action in the United States.

What the End of Affirmative Action Means for Individuals and Institutions

What Does This Actually Mean for You?

For students, admissions will now focus more heavily on academic records, essays, recommendations, and extracurricular achievements. Applicants may still describe challenges related to race, but those experiences can only be considered as evidence of individual character or resilience, not as a basis for admission.

For employees and contractors, Trump’s 2025 revocation changes compliance obligations. Companies once required to file detailed affirmative action plans with the federal government may see fewer administrative requirements, but they must still avoid intentional discrimination and remain vulnerable to lawsuits if their internal policies appear to favor specific demographic groups.

Your Legal Rights in Texas

Texas has years of experience operating under affirmative action restrictions. After Hopwood v. Texas (1996), public universities were barred from considering race for several years, which led to the creation of the “Top Ten Percent Rule,” guaranteeing automatic admission to state universities for students in the top ten percent of their graduating class. That rule still exists and continues to serve as a race-neutral mechanism to broaden access, particularly benefiting students from underfunded high schools. Following the 2023 ruling, Texas institutions must remain fully race-neutral, but their existing systems make the transition smoother than in many other states.

Long-Term Legal Questions

Several legal questions remain unresolved. Will scholarships restricted to certain racial groups survive constitutional scrutiny when administered by public institutions? Could personal essays that indirectly reveal an applicant’s race be considered impermissible proxies? How far will courts extend the 2023 decision’s reasoning into employment law, federal contracting, or corporate DEI programs?

These questions indicate that while the Supreme Court has closed one chapter on race-conscious policies in education, the broader legal debate over affirmative action in employment and contracting is likely far from over.