Autor: Shelby Benavidez

Abogado colaborador: Casey Kelly, legal director

Storytelling may seem like an art reserved for authors and filmmakers, but in the courtroom, it’s a vital skill of persuasion. For trial attorneys, stories create a framework for truth.

Casey Kelly, legal director at Daniel Stark Injury Lawyers, believes that the best advocates are storytellers. “Storytelling in law and advocacy really is taking the facts and distilling them into a narrative,” he says. “A narrative that’s compelling enough for the audience to not only stay interested, but feel called to action.”

In Kelly’s view, storytelling doesn’t replace evidence – it translates it. Facts on their own can feel cold or disconnected. But when woven into a human narrative, those same facts can clarify, persuade, and inspire accountability.

Turning Facts into Feelings

Lawyers deal in facts, including documents, data, and testimonies, but juries appeal more to emotion. They make sense of information through stories that feel authentic and relatable. That’s why, Kelly explains, storytelling is about taking our clients’ journey and turning it into a story that makes the jury feel their pain.

Transforming information into a narrative is what separates a technically sound argument from a persuasive one. You can have all the facts in the world supporting your case, but if the jury doesn’t understand it (or they just don’t care), it won’t resonate.

The Anatomy of a Legal Story

When Kelly prepares for trial, he doesn’t just think about evidence and witnesses. He thinks about structure – the same kind of structure used in movies and literature.

“In the context of personal injury, the elements really are a hero, a villain, and a conflict,” Kelly says. “The hero is always our client. The villain might be the defendant, the company that employed the defendant, or even the insurance company in some cases. The conflict is the injury we need the audience, which is the jury, to help resolve.”

In that story arc, we need the jury to play an active role in being part of the resolution. They can’t be just passive listeners.

“The story is going to have our hero, who’s been injured by the villain, and we need the jury to help make it right because the villain’s not making it right themselves.”

Who Plays the Villain?

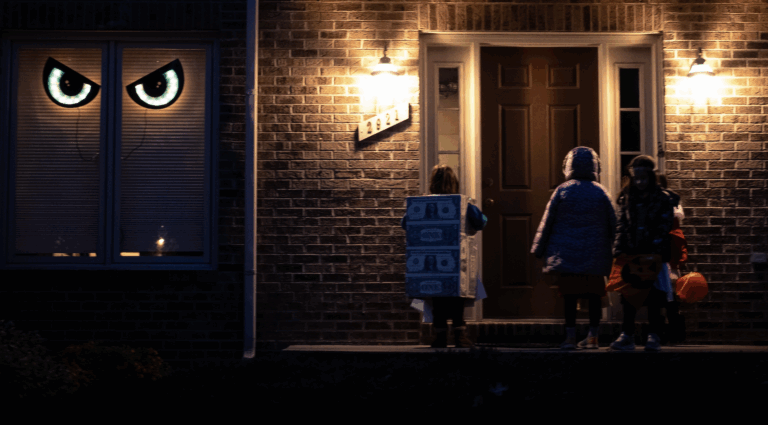

Of course, not every case has a clear “bad guy.” Sometimes, the opposing party didn’t mean to cause anyone harm; they took their eyes off the road for one second. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a story to tell – it just means the narrative has to go deeper.

"Maybe they’re not the villain in the traditional sense,” Kelly explains. “They didn’t do something horribly egregious. It was just a simple mistake. They didn’t pay attention for a second, and that caused the accident.”

In those cases, the conflict shifts from wrongdoing to responsibility.

“Why are we at trial? Because they haven’t made it right,” he says. “Somebody can be a villain just by the fact that they haven’t fully accepted responsibility for the damage they’ve done.”

It’s a subtle but powerful reframe that keeps the focus on accountability and justice rather than blame. Our clients have lost a lot, they shouldn’t have to take on the financial responsibility of recovering from their injuries.

How Stories Move Juries to Action

At trial, the story you tell guides the jury through the facts. Without it, evidence can feel abstract. The picture you paint should help jurors understand exactly what happened and how it has impacted your client’s life.

“During closing arguments, I present the full story,” Kelly says. “I remind the jury who the hero is, what conflict they’re facing, and what the jury can do to make it right.”

By the time the jury retires to deliberate, they shouldn’t need any more information. They should already know your client’s story – who they are, what they’ve gone through, and why helping them matters. The goal is for the story to stick, so they feel compelled to make your client whole again.

“If I’ve built a story where my client is the hero and the other side is the villain, and I can present the conflict in such a way that the only resolution is to put money in my client’s pocket,” Kelly says, “then the jury’s going to want to help my client.”

The objective is to leave the jury fully informed and engaged. Effective storytelling bridges understanding and empathy, making the path to resolution clear.

Turning Storytelling into Measurable Impact: The $41.4 Million Verdict

Kelly vividly remembers a case that demonstrates the power of storytelling in law and how it can translate a client’s catastrophic journey into measurable outcomes. This case resulted in a $41.4 million verdict, but the story behind the number reveals why the narrative mattered as much as the evidence.

“We had heroes – incredible, amazing clients who were salt of the earth people,” Kelly says. “And we had villains – a drunk driver who blew through a stop sign because he was blackout drunk and crashed into our clients.”

The narrative went deeper. The driver’s employer, who had previously allowed the individual back to work despite previous drunk driving offenses, became an additional layer of accountability.

“We had another villain, the owner of the company,” Kelly recalls.

By framing the case as a story with heroes, villains, and clear conflict, the jury could see the real-world impact. Kelly explains how the storytelling made jurors realize that the lives of these clients were changed forever.

“Our clients were just going about their daily lives,” he says. “And the consequences of the villains’ actions were catastrophic. The story made the jury understand the magnitude of what happened – and why it demanded a decisive response.”

The jury didn’t just see medical bills, lost wages, or pain and suffering – they saw how the actions of the defendants cost our clients their quality of life. That understanding allowed them to put a value on the profound and irreversible change to the clients’ world.

“It wasn’t just about the numbers,” Kelly emphasizes. “It was about justice, told through the lens of a story that jurors could believe in.”

When people understand the human stakes behind decisions, they can make choices that align both empathy and accountability with measurable outcomes. A truly compelling story should drive action, motivate decision-making, and put value on what truly matters.

Crafting a Story Before Trial

While the courtroom might be the stage where storytelling shines brightest, its impact can begin much earlier in conversations with mediators, opposing counsel, or insurance adjusters.

“Being able to put what happened to our client into a story and then sell it to a mediator or an adjuster or opposing counsel – that helps build our case,” Kelly says.

In civil litigation, both sides usually know what evidence will be presented. There’s no real mystery. However, the way those facts are delivered can transform a good outcome into a great one.

“I can let the defense know, ‘Here’s the story I’m going to tell. Here’s what the jury’s going to hear,’” Kelly explains. “If the defense believes that story will resonate, they’re probably going to put more money on the table earlier. That shortens the client’s journey to recovery.”

In other words, a strong story can lead to faster settlements and better outcomes without ever stepping into a courtroom.

What Young Lawyers Can Learn from Storytelling in the Courtroom

For young lawyers, Casey Kelly’s advice is simple: go watch trials. “If you have the time, which I hope you do, go sit down in the courthouse and watch opening statements, closing arguments, and jury trials,” he says. “You’ll learn just as much about good storytelling as you will about bad storytelling.”

Kelly believes there’s no better classroom for understanding narrative than a courtroom. Watching how attorneys capture – or lose – a jury’s attention teaches lessons that go far beyond law. “We live in a world where a 60-second TikTok is too long for most people to watch,” he explains. “If you don’t grab your audience’s attention quickly with something compelling, you’re going to lose them.”

The strongest communicators open with impact, stay focused on their core message, and resist the temptation to chase competing narratives. “Don’t play in the defensive sandbox,” Kelly says. “Know your story, tell it well, and don’t get distracted.”

In essence, storytelling requires clarity, confidence, and connection. For young attorneys, learning to observe and apply those principles is where great communication begins.